Review: Wicked (2024)

this space intentionally held to acknowledge the lyrics of "defying gravity"

I went to see the Wicked film with my family this weekend. As I watched, I thought about how many layers of adaptation it took to bring us to this film. This movie is an idea refined over more than a hundred years through a series of previous adaptations across multiple mediums.

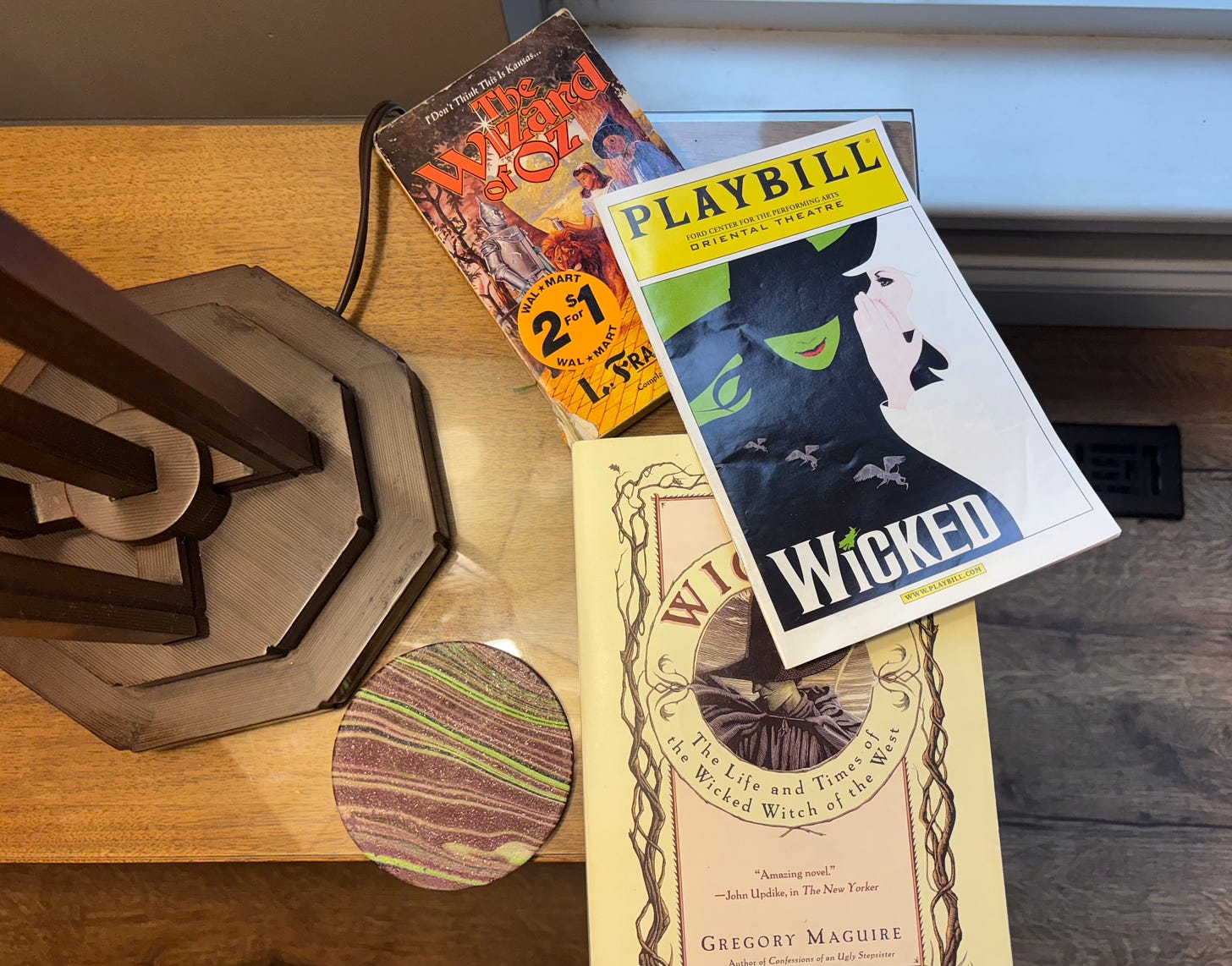

The bottom layer is L. Frank Baum’s The Wonderful Wizard of Oz novel, published in 1900. I read this book and some of its sequels in the mid-2000s when I was a child, in the wake of the Wicked musical hype. I didn’t love them that much, but I read a lot of YA fantasy at this time. Like many of the twenty-first century YA fantasies I read, this book is a story of a character from our world, in this case Dorothy from Kansas, discovering a new more magical world. She goes on a quest in that world and learns her own power, then goes home. That’s a powerful promise to a child, searching for art that can bring strength to their own life, and one of the reasons The Wonderful Wizard of Oz was a commercially successful book.

It also was successful because its fantasy was compelling. The fantasies of 120 years ago are different from the fantasies we have now; maybe even more different than social manners, or technological landscape, or the many other lost parts of the world that older literature can create windows back to. That’s to say I’m not sure I can understand The Wonderful Wizard of Oz as a fantasy on the terms it was written. This book was written before the refinement of fantasy into the mass-culture genre it is now. It feels like a bridge towards the sprawling complex fantasy worlds we know now from traditional folk-fairytales. The primal folk-fantasy of Oz, like a witch melted in water, cities of tiny munchkins, and talking scarecrows, is what drove this book’s popularity, and a crucial element of every adaptation after. These elements feel eternal, but with how far the genre has gone they also feel quaint and small. I find it hard to imagine a contemporary child getting lost in this world as a sincere fantasy, but they remain powerful elements.

While this book is a proto-fantasy, it’s also subversive of the fantasy genre. The titular Wizard, who Dorothy expects to save her, is a fraud, from the same banal America that she’s from, tricking the naive inhabitants of Oz with smoke and lights into thinking he’s more powerful than they are. The reveal of the fraudster wizard is at the heart of every Wizard of Oz adaptation, even the later Wicked, which claims to challenge the Wizard of Oz’s simplistic narrative. Though the fantasy of Oz persists through this subversion, it’s a harsh blow to the fantasy to reveal that what the hero had hoped might save them was never real.

The next layer of adaptation is MGM’s 1939 film The Wizard of Oz. This film is a faithful adaptation of the L. Frank Baum novel. If it changes anything, it makes the tone less subversive. The Wizard is less of a huckster than in the books; his fantastic Emerald City really is Emerald in the movie, where in the book it’s pure white, only appearing Emerald because of green glasses that the wizard tricks Dorothy and her friends into wearing.

This movie is still a fantasy, but it’s also a spectacle. At the time of release, this was one of the more extravagant but simultaneously accessible movies that Hollywood had produced. It famously transitions from black-and-white to color when Dorothy leaves boring Kansas and reaches Oz. The Wizard of Oz plays up the colorful beauty of Oz as an image on the screen to marvel at. The yellow brick road, the fantasy munchkins, and other fantasy elements from the book become more magical when it’s put on the screen. I think it was the capability of 1939’s technology and Hollywood practices to make a story like this visually compelling that drew it to adapt this 40-year-old novel; the visuals fit their capabilities perfectly.

In addition to its initial 1939 theatrical release, this film was also famously aired on American television networks starting in the 1950s and for decades after. This was a time when television was becoming the most accessible ways to consume media. Because it was shown so many times on television, The Wizard of Oz became a fixture in the American consciousness, one of our most widely known pieces of media. This is far beyond the impact of the original L. Frank Baum book.

Based on this fixture of American consciousness, Gregory Maguire wrote the novel Wicked, in 1995. The concept of this book is an exploration of the antagonist of the Wizard of Oz book and film. In the prior versions of the story she’s just “The Wicked Witch of the West”, pure evil without redeeming qualities. Maguire writes this book in an attempt to understand evil, backfitting a sympathetic prequel to explain why “the Wicked Witch of the West” could have been the way she is. Maguire gives the witch the name Elphaba, when the witch was totally unnamed in the prior layers of the stack, just a villain for Dorothy to defeat.

This is the only adaptation that I have not personally consumed so I won’t try to say too much. I have not read the book Wicked; having listened to the musical a few times reading all of the words of its narrative doesn’t sound interesting to me. My impression is that it’s a book about idealism and the best ways to do good, in a more complex and adult political fantasy set in the world from the original Wonderful Wizard of Oz. Elphaba, the wicked witch of the west, is an outcast all her life, because she is born with green skin. She uncovers a secret conspiracy to stop the animals in Oz from speaking. She tries to get to the bottom of it, while growing up and learning her own power. She spends time with Glinda, who also appears in the Wizard of Oz book and film as the Good Witch of the South, serving guide to Dorothy in her conflict with the Wicked Witch of the West.

The Wizard of Oz is still a figure who our protagonist hopes might save her in this book. Now he’s not only a huckster, but he’s also Elphaba’s father, a father who let her down in the traditional oedipal narrative. He is part of the conspiracy, wants Elphaba for the power she really does possess. But she has purer ambitions than him. When her father lets her down, she becomes “The Wicked Witch of the West”, and then tries to lead a movement against him to save the animals on her own.

Wicked (2003) was a Broadway musical adaptation of this 1995 book, with songs written by Stephen Schwartz. Most books don’t get adapted for Broadway, and though the Wicked novel was commercially successful I don’t think it was obviously a candidate for a Broadway musical. That the The Wizard of Oz film is such a fixture in American consciousness helped here. Broadway musicals are a very competitive medium, and every bit of brand recognition helps. References to a big well-known American story like The Wizard of Oz ensured Wicked would be a low-risk Broadway musical.

From the novel’s sympathetic retelling of the witch’s life as political fantasy, the Wicked musical mines out a smaller and more theme-oriented story. The larger political fantasy world is stripped back, leaving an exploration of idealism, self-perception, and friendship. The story is centered around Glinda, the good witch, and Elphaba’s friendship. It opens with the death of the Wicked Witch, which happens at the end of the narrative of The Wizard of Oz, and then flashes back to far before that narrative, to the two witches as children together. Though one is the good witch and one is the bad, they have childhoods entangled together, each of them striving to the best they can in the world. Elphaba is idealistic and combative, wanting to change the world, while Glinda is conciliatory and wants to be kind. Glinda is also much more beloved by everyone around her, beautiful and blonde, while Elphaba has green skin, a metaphor for disability or race or whatever else you as a reader want it to be as an intractable fact of yourself that cannot be changed.

Each of the play’s two acts climaxes with songs about Glinda and Elphaba’s unique friendship. First, “Defying Gravity”, where Elphaba self-actualizes against the Wizard and decides to go off on her own, offering Glinda the chance to join her. However, Glinda chooses to stay, becoming Elphaba’s explicit enemy in the conflict with the Wizard. Then, in “For Good” Glinda and Elphaba meet for the last time and reflect on how their time together has shaped each of them.

The Wicked musical was successful, shortly becoming one of the most famous musicals ever. It’s played continuously on Broadway to this day, twenty years after its release, and will likely play a lot longer. Its style and tone was influential on high-budget Disney musical films, especially Frozen (2013), which casts the actress Idina Menzel, who played Elphaba in the Wicked musical, as its lead, and has a similar message of sisterly bonds for female self-actualization.

Finally, we have the new Wicked film (2024). Of all the layers in the sequence, I think this one is the least ambitious, despite having the largest budget. It takes the 2003 Wicked musical and transfers it faithfully to the screen, staying true to the tone and content. It expands on some areas, but these additions feel like an expression of such strong love for the original musical that they can't help but indulge in spending more time with it.

If this new adaptation changes anything, it makes Wicked more accessible to the younger audience who would watch musical movies. Wicked's novel was written for adults, and the musical likely targeted an adult audience as well, as adults are typically the audience for brand new Broadway musicals. But this adaptation is rated PG, there were a lot of kids in the crowd when I saw it, and they played a commercial for the upcoming Disney musical Moana 2 just before the movie started. They age down the tone to an audience that might have interest in the content. This adaptation, made 21 years after the Wicked musical, better understands its cultural and market niche, from the way a story like Frozen based on Wicked’s influence was so relevant to young girls, and the way Wicked itself was relevant.

Though it’s faithful to the prior layer in the sequence, and isn’t doing much new, this adaptation layer still can justify its existence because the Broadway musical Wicked is inaccessible. Musicals are an art form that exists primarily on physical stages in major cities, with expensive tickets and significant time commitments to consume the art. The Wicked musical does have a soundtrack, which in some ways is its cultural remnant more than its stage perfromance, but there’s a significant amount of dialog in the musical and much of it is lost in the soundtrack. Film is permanent, it can mix music and dialog, and anyone who can afford a streaming service can watch it. Especially for the younger audience it feels like it’s trying to reach this is valuable, even if the movie isn’t doing anything fresh.

Paul Skallas tweets and writes about “stuck culture”, saying that our contemporary culture exists in endless reference to itself. He cites Hollywood's careful calibrated churn of sequels that are guaranteed to be commercially successful as an example of this. This film, Wicked (2024), is certainly an example of that. But I think this stack of adaptations also serves as a counterexample of just how long culture has been “stuck”. Even in 1939, Hollywood adapted a 1900 novel as their big spectacle movie. In the 1950s, networks aired fifteen-year-old movies on TV. And in the 1990s and early 2000s, The Wizard of Oz was chosen as a commercially safe reference point for new spinoff properties.

Yes, this new Wicked adaptation is especially safe and restrained. Not just safe in reference to the Wicked musical, it also leans on references to the original Wizard of Oz book and film narratives to which Wicked serves as a prequel. There are many jokes that rely on dramatic irony of events in the original Wizard of Oz narrative, like how Elphaba will eventually be melted with a bucket of water by Dorothy. There are a few slightly silly prequel moments, such as explanations for how Elphaba got her pointy witch hat and how the yellow brick road became yellow. I think these prequel reference moments are not great, and undermine what is otherwise an independent narrative. In many ways, Wicked is more meaningful than The Wizard of Oz in our contemporary culture, and this new film doesn't need to rely on such an old story

But my point is we’ve been doing safe references to existing properties for a while. That doesn’t justify lack of creativity; I think art that is totally unrestrained, like the original Wonderful Wizard of Oz fantasy book by L. Frank Baum, is more important than adaptation. That’s the real creative act here, but there were creative artistic touches at every further step along the way, especially in the Wicked novel and musical. They changed the original narrative and made it into something new, with a more moral subtlety than the original Wizard of Oz fantasy. This film does not do that; it just transposes the musical onto the screen. But it wasn’t trying to do more.

I saw your tweet about living rooms and now find myself enjoying this post about Wicked. The Internet is a cool place.

thanks, i was curious. seems like something people are really into