My First Book opens with the C.S. Lewis quote “for the present is the point at which time touches eternity”, which feels like this book’s mantra. The writing that follows leans on internet language, the language of a present, in a way that feels like the defining feature of the book. I haven’t been reading much lately, since I’ve been spending way too much time on the computer and the physical manifestations of the computer in New York City, but when I found a moment to read this book, the internet language of My First Book was easy to get through. I carried the book around on the subway and could get through at least one story every time I opened it.

For some background, Honor Levy and I are Twitter mutuals and have been for a while. We’re the same age, and have been posting around similar people for a long time. She moved to New York City before I did, and became part of “the downtown New York scene” that I sometimes see in real life now that I’m here, but she lives in Los Angeles now. Her internet presence is also wide-ranging, not just Twitter but also Instagram and TikTok and podcasts, and I didn’t follow all of it as it was happening. So we existed in the same world, but I didn’t know much of what was going on with her until My First Book came out.

I’m unsure what to call My First Book, besides a book, and that’s what I want to write about in this review. Short story collection is the closest term in our current vocabulary, but this is only kind of a short story collection. The longest section of My First Book by far is “Z is for Zoomer”, which is a glossary of Honor’s takes on different Gen-Z internet words: sometimes definitions, sometimes jokes, sometimes art, and sometimes opinions. It takes up 50+ pages of the book’s 200 pages. Technically, it can be argued to be a short story, because there are two older male millennial characters in a frame narrative who sometimes appear in the explanations of the internet words, but I don’t believe in technicalities in art. The section is well-written and makes Honor Levy’s command of internet-English very clear, but it’s more a glossary than a short story.

“Short story” also feels wrong as a description for most of the rest of My First Book. The stories “Love Story” and “Brief Interview with Beautiful Boy” and “Pillow Angels” feel more like riffing on a subject in internet language jokes than stories. “Love Story” is about a boy and a girl who’ve never met irl in love online, “Brief Interview with Beautiful Boy” is about a desirable(?) boy, and “Pillow Angels” is about girls at a sleepover. These pieces are abstract, without much plot beyond the few word summaries I gave. They’re rhythmic, with lots of repeated sentence structure, and have a lot of jokes, from hapologroups to Epstein Island. There’s a lot of edgy internet language, but Honor is also well-versed in Tumblr and Reddit and Facebook, so her writing feels broad across the whole internet. I can see these three pieces doing well at downtown Manhattan readings because you don’t have to pay attention to the whole thing to get each individual joke. These feel closer to poems or songs, sequences of ideas about a theme.

My First Book also includes “Good Boys”, which appeared in The New Yorker as a “flash fiction story”. It’s just a few pages long, with the least digital language of any piece in the collection, only a brief “the sky was pink like Kirby”. It’s describes young boys and girls on a roof in Paris, at a moment where the boys describe certain women as dogs, but not these girls on the roof with them now who “get it”. And so it’s piece of writing about how it feels to be a girl who’s accepted by these boys. It’s a good piece, but it’s a stretch to call it a short story, and The New Yorker didn’t call it that. It feels more like an image; a single moment that Honor expounds upon over a few pages.

One of my favorite pieces in the collection is “Hall of Mirrors”, which describes a upper-class college girl who volunteers at an elementary school, near a factory that produces glass, tying it back to the history of mirrors, and the Hall of Mirrors at Louis XIV’s Versailles estate, which the narrator visited when she was younger and these kids might not visit. This one is one of the closest to a traditional short story, although like “Good Boys” it’s more explaining a moment. The way it switches between fiction and history is a great example of what the internet can do for writing; it feels like a little tiny bit of Sebald.

“The End”, one of the last stories in the collection, is a musing on the apocalypse, often circling back to the Yeats poem “The Second Coming”, which is often referenced on the internet. It has some lines about a “Mormon supersoldier” who saves the female narrator of the musings, which again technically gives it a plot, but he’s not that important to what the story is doing. The story that follows it, “Halloween Forever” is also about the apocalypse. It opens with a list of eerie parts of the present, like “drone strikes on weddings” and “the very normal entries nestled amid the racism on Dylann Roof’s blog”, sort of like Bo Burnham does for 6 minutes in his song “That Funny Feeling”, although Honor is a better written than Bo Burnham. Then the story goes on to into brief autofiction about a Halloween party in Brooklyn, and then goes it on to talk about the viral Facebook event where millions of people RSVPed that they were going to storm Area 51. It’s a dissonant collection of ideas, thematically united together, in a way that also feels united with the prior story.

In Arielle Isaack’s review of My First Book for The Baffler, she describes My First Book as “prose that otherwise resents itself for failing to replicate the vibey ephemerality of a post”. And there’s something to that thought, but I don’t see My First Book as a complete failure to replicate a post. The translation between post and traditional printed writing is difficult, but I don’t think it’s impossible. And more than that, I think it’s important, for the sense of the book’s “present touches eternity” mantra. Posts are what people care about now; so it matters to preserve them outside of ephemerality, into something more concrete and tangible. A book can do that.

The post is a much wider medium than a novel. A post can be a diary entry, a post can be a manifesto, a post can be a poem, a post can be a joke. Most posters mix forms. Honor’s book jumps between a lot of different forms, trying to show all of the different kind of things a post can do. I’ve been thinking about My First Book in the context of other books by internet personalities, like sighswoon’s Notes on Shapeshifting and Bronze Age Pervert’s Bronze Age Mindset. Neither of those books are are a novel, or a manifesto, or a short story or poetry collection, but something in between. These books have value for making the world of the posters more permanent and more clear, even though they’re not written in traditional forms.

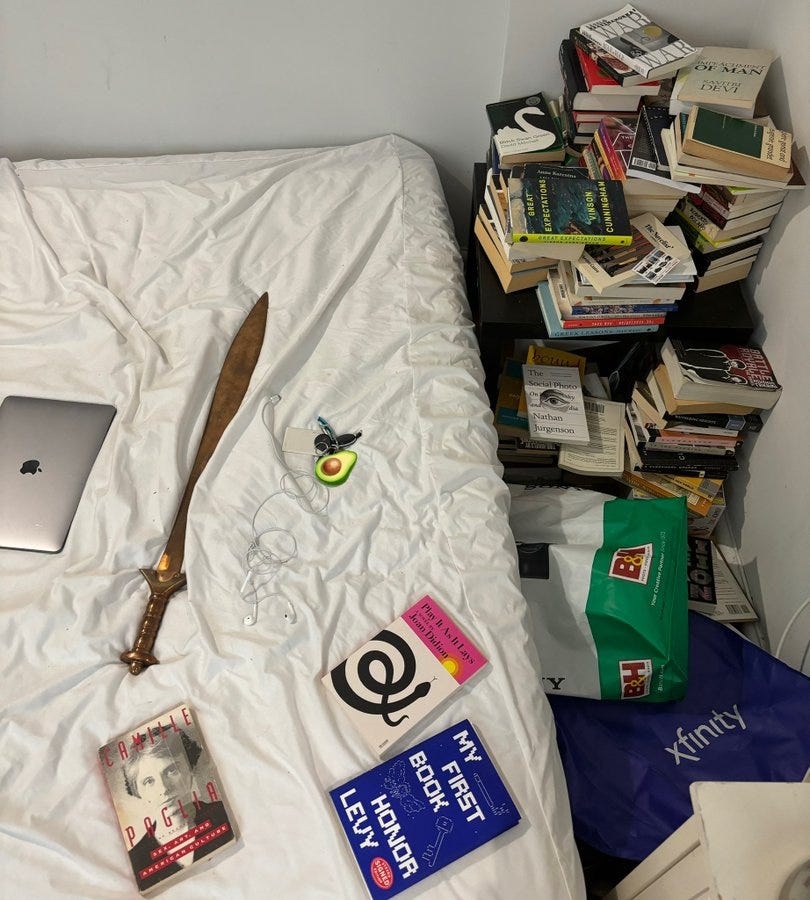

If you’ve never read Bronze Age Pervert or sighswoon you can pick up their books and get the gist of what they’re about. And even if you know them well, spending continuous time in their mind reading their longform writing makes that world a lot more clear than scrolling past a few of their sentences. Also, it’s nice to have a physical manifestation of the posts you care about, a book-object sitting around in your house to remind you that the poster matters to you. This is true even if the book isn’t a traditional one. A book is just a string of sentences; it has a lot of possibilities beyond existing forms.

I sympathize with some of the criticism of this book, that My First Book achieves its formal goal of putting internet language in traditional writing more than it says substantive things about it. I don’t have any thoughts on the “themes” here; about the culture war, about isolation on the internet, about the potential for empathy on the internet. Honor seems kind in her writing, and I’d like to read more, but I don’t think this book is totally complete. My First Book captures a particular moment of the internet by being so bound in up in capturing its language, along with how Honor feels about this moment. The book is not fully Honor; it’s her voice mixed with the internet. I don’t know if I learned Honor’s world the same way I learned the world of sighswoon and Bronze Age Pervert through their books, although I did know those posters better before I picked up their books.

There’s meaningful criticism to be made of poster writing as shallow. Though Honor Levy definitely has read a lot of novels, My First Book doesn’t try to be a novel, obviously. Though I love posts, I still believe in the power of the novel, I’m eagerly awaiting the next Franzen, it could possibly fix me. Novels explore their topics in more depth, spending more time with characters, taking them through a narrative. Short story collections are the little brother of novels, where authors in the olden days would go to write in short form before the technology was there for posting. Maybe it makes sense to start there as an aspiring young writer but they’re a very particular form. Some internet writers work well in the short story form, like Delicious Tacos, but I don’t think it’s the only answer. The poster book is much riskier and more nascent form, but I’m really excited about the potential it has.

Basically, I don’t know if My First Book needed to be a short story collection to achieve its goals. I think that if My First Book were less concerned with feeling like a short story collection, and more with feeling like Honor’s world, her world could have been more clear. But I’m also optimistic about the present that the book describes, and what Honor can write in the future. A lot of the writing here is great, and points in exciting directions. Honor is twenty-six, I’m twenty-six, it’s fine. We have time, maybe.

The poster wants involvement not permanence

Honestly I'm shocked that more poster books like this haven't come out already. (If they have, I haven't heard of them.) Lines like "the sky was pink like kirby" even if ironic strike me as shockingly organic to the pop culture encyclopedic age we're living in; it's almost as if current literary style is trapped in this fake movie set ghost town pretending to be of a time and place that none of us live in and never have -- where there is this quiet, unspoken pact NOT to encyclopedically reference the internet discourse and pop culture of which we're all perfectly aware and reference with regularity in informal discourse, as if to do so would be "unliterary" or somehow ruin the glossy, timeless, internationalist vibe we're going for in an "official" publication. For better or for worse "Kirby" is a more immediate frame of reference for a lot of people compared to, say, a species of flower in the natural world.

I get people not wanting their work to become immediately dated. But that's the problem -- as far as the internet is concerned, your work IS immediately dated. Because it's been "published" and set in stone instead of being a living, reactive discourse online. I for one hate the glossy timeless internationalist writing style, as soulless and devoid of texture as Corporate Memphis is visually. Not that everyone has to make Nintendo references to overcome it -- obviously what you choose NOT to mention is as artistically important as what you do -- but I think writers should take the internet as an inspiration to be far more wide-ranging with what sort of popular and niche indexes of culture they draw upon for their personal invention, and cobble together to form their own unique scrapyard sculpture parks in prose.